Goodbye, Julio.

I recommend you read while listening to this.

Buenos Aires is a plate of flan with dulce de leche and a spoonful of cream. Buenos Aires is a song belted out over the clicks and screams of a bandoneon. Buenos Aires is a small table on a busy street, preferably a corner. Sometimes Buenos Aires is all of these things at once; sometimes, when the summer heat beats down on my skin and the humidity pulls out the air from my chest, I forget that any of this exists. Happiness washes over me all over again once I rediscover it—as if it were my first flan, my first taste of folklore, my first time meeting with friends for few bottles of wine.

I never really know how to respond to Argentines when they ask me why I’m here. “Do you like Argentina?” Obvio, I think to myself, I just told you I’ve been here for more than a decade. Yet this question, implying that I live in a country that I both like and loathe, makes me feel accepted in a way, an acknowledgment of my adopted Argentinidad, my comfort with contradiction.

What I usually tell people is that the United States isn’t perfect; that it isn’t what they imagine. I tell them how hard it is to maintain a decent quality of life there, too. I make up some speech about universal healthcare and free education. I’d rather tell them that I like pizza and wine, the bookstores that are everywhere, that I can read in a café for hours and only order an espresso. I would prefer to tell them that I like how friends are like a second family and that having a million projects, that you can never stand static, is something that I see as a virtue and not a punishment.

The summer before I moved to Buenos Aires I lived in an apartment above my grandparents’ garage. For six months I worked three jobs, usually two on the same day, and took a Sunday off every other week. Every night I’d sit at my desk and fill in a map of the city in my head with all the things that I wanted to do, all the foods I wanted to taste, the musicians I’d see live, the art I could look at up close. I danced alone to this mixtape by Chancha Via Circuito so many times that if it were an actual tape, it probably would’ve caught fire from being listened to so many times.

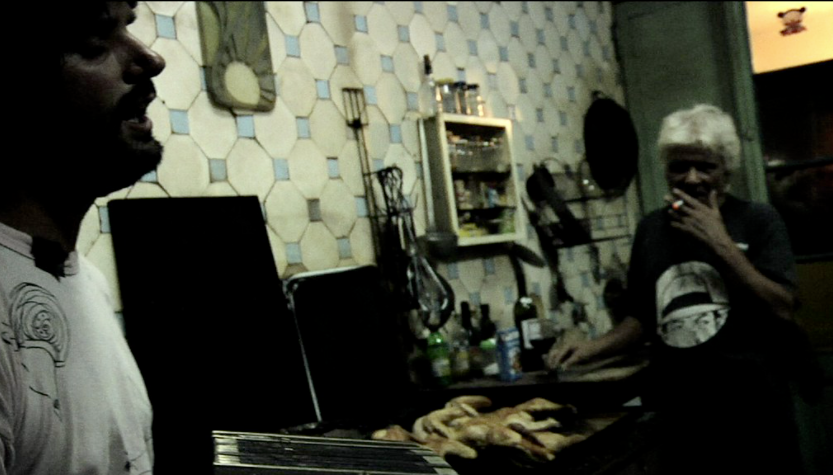

Vincent Moon filmed this music video the month that I arrived and released it a few months later. That was a difficult year. My grandfather passed away, my brother-in-law took his life and my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. The way that Moon captured Tomi Lebrero singing Cuando a caballo spoke to me and the nostalgia that I wanted to be wrapped into. That was the city I wanted to know, the friends I wanted to have.

no me despierten pues quiero soñar /

que al besarte me vuelvo otra vez /

a nuestro amor y soy niño otra vez

don’t wake me I want to dream /

when I kiss you I return /

to our love and I am a boy again

I showed that video to everybody and asked if they knew the place; if they recognized the framed underpants hanging on the blue-tiled wall; if they had ever seen the man with white mullet standing in the corner. Months passed without a single clue.

Through a very long chain of happenstance, I would eventually arrive. The white-haired man was Julio, this was Lo de Julio (or Julio’s Place). That first night I shared a table with a cop named Jorge who leafed through an infinite scroll of drawings, mostly horses, that he feverishly drew night after night. Somewhere there are pictures of me and my friends wearing Jorge’s bulletproof vest and hat. Jorge liked to tell the story about a curator for the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano that came to eat one night and bought one of his paintings. “I’m not a cop,” Jorge proclaimed. “I’m a cop with a painting hanging up at the MALBA.” I never knew if that story was true but who cares if it was.

There were taxi drivers whose names I have long forgotten, artists, travelers, people with lots of money, people who barely made it to the end of the month, expats’ parents in states of awe and alarm, hippies with medical insurance, hippies without. There was no hierarchy.

The doors opened when Julio felt like it. The menu was always milanesa with fries. There was the occasional roast chicken crowned with leeks beat down with butter or tortilla de papa if he was feeling altruistic. There was always salad with lettuce, big tomato chunks and onions that were almost always too acidic. He started cooking when he was in the mood to and we often ate around midnight. Being allowed to serve your own fernet or grab a liter of beer from the fridge was a badge of honor. A level unlocked. There was a book of Kabbalah that told you your fortune and a ghost that lived in the basement where Julio and Jorge slept. It was all a part of the show. If you were open to receiving Lo de Julio exactly as it was, you were welcome.

NOT A SUBSCRIBER BUT ENJOY READING MATAMBRE?

BECOME A SUBSCRIBER OR SUPPORT WITH A SMALL DONATION

Julio had the gift of seeing people. He could look at you after just meeting you and understand the most intimate pieces of you, things you’d barely tell yourself. He could articulate exactly what you needed to hear often in a single sentence. It was the first place that I felt welcome. The first place where I felt like I really saw Buenos Aires. The first place where I felt like Buenos Aires saw me. To most people I met, I was a curiosity bordering on a novelty, I felt like a doll, but to Julio I was another player in his cast of personalities.

Lo de Julio was the first place that I ever cooked tacos for a public outside my own home. As far as I know, I am the only person that he ever let touch his stove. He refused to let me repeat it. Not because I had done anything wrong but because he knew that I needed that push, that he had to give and then take away for me to take the next step. This is the way the country works, too; the only thing that lasts is that everything is always changing. Years passed before I realized what he had given to me. I don’t know if he ever knew what he’d given me.

A lot of the neighbors weren’t kind to Lo de Julio. They frequently sent the police to cut the music but I don’t think they were upset about the noise. To me the complaining neighbors were from another Buenos Aires, a Buenos Aires that doesn’t really exist, an indignant Buenos Aires that lives inside the negation of reality. It bothered them to see someone who was true to himself and to this place, true to where they both stood in this world. Someone who acted with total freedom and pushed aside what it meant to be an old man in an uppity neighborhood. He didn’t give a fuck what it meant to run a bar, he didn’t serve anyone’s expectations except his own. To me, Lo de Julio was Buenos Aires, an essence I can try to put into words: the people’s frankness; spontaneity as routine; having a conversation with anyone that you cross paths with; a shared language, no matter your social position, built atop the food, the crisis, the heat, the ritual, the cleverness required to live here; the beauty of the grime and imperfection of a place that had and has life; the contradictions that are worn with pride and never hidden.

I realize now that maybe I arrived late to the party. That the complaining neighbors are advancing. Their city is sanitized and insipid. Often an imitation of itself. Chain coffee shops, chain pizzerías, chain bookstores. A city that is indistinguishable and impersonal. This is not Buenos Aires and it never will be.

A few months before COVID I went to watch Tomi play. I almost didn’t. It rained hard and we all huddled together underneath the torn awning. Water dripped between us. I played with his cat, Bienvenida, who ran in and out of the plants that separated the restaurant from the street and the rest of the world. I introduced myself to Tomi and told him that I had gone to see him play half a dozen times but that it meant something special to see him play in that kitchen, that it brought everything together. He finished the set with Cuando a caballo and everyone sang the final part together, la lalala lalala lalala.

I didn’t know that would be the last time I’d visit Julio. I stopped coming around during the pandemic. His life had suddenly caught up to his health and I didn’t feel comfortable crossing paths with him. He passed away a few months ago. At his wake I brought chocolate truffles, the dessert I made the time that I cooked for him, the truffles that he liked so much. There were conversations about recreating Lo de Julio: a cafe or bar that would continue his legacy. Obviously, I thought to myself, that’s impossible. I smiled and nodded and vowed to never go back.

The bar has now turned into a specialty coffee shop; the fifth to open this year in the neighborhood. It is supposedly an homage to Julio. They ripped out all the plants, scraped the stickers off the windows and took down the striped awning but the blue tiles shine again, the bathroom doesn’t leak and the mold has been scraped off the ceiling. It is now a place for people who would have never gotten along with Julio. The old prudes that called the cops because we sang and laughed on a Wednesday night; now they have another place to eat carrot cake with their flat whites. I can hear him cackling about it somewhere.

I did walk past once by accident. I stood there frozen, looking around, wondering where all the art on the wall had gone. The barista asked what I wanted: I shook my head, said “que verga” under my breath and ran off. I later complained to a friend of mine: Is this what it means to grow older? Things are changing and I don’t like it. Now I realize it isn’t about age but about a sense of belonging. I belong here. Lo de Julio is a piece of me and now it’s gone, physically at least. Buenos Aires is gentrifying and becoming more hostile to places like Lo de Julio, making it harder for them to survive and be better.

Tomi is now a friend of mine. He has written hundreds of songs. In 2019, he released an entire album every single month. He always messages me when he has a concert coming up. Although Cuando a caballo is a single ring in a big tree of music when the concert is small, he likes to tell the crowd about how I found him before playing my favorite song.