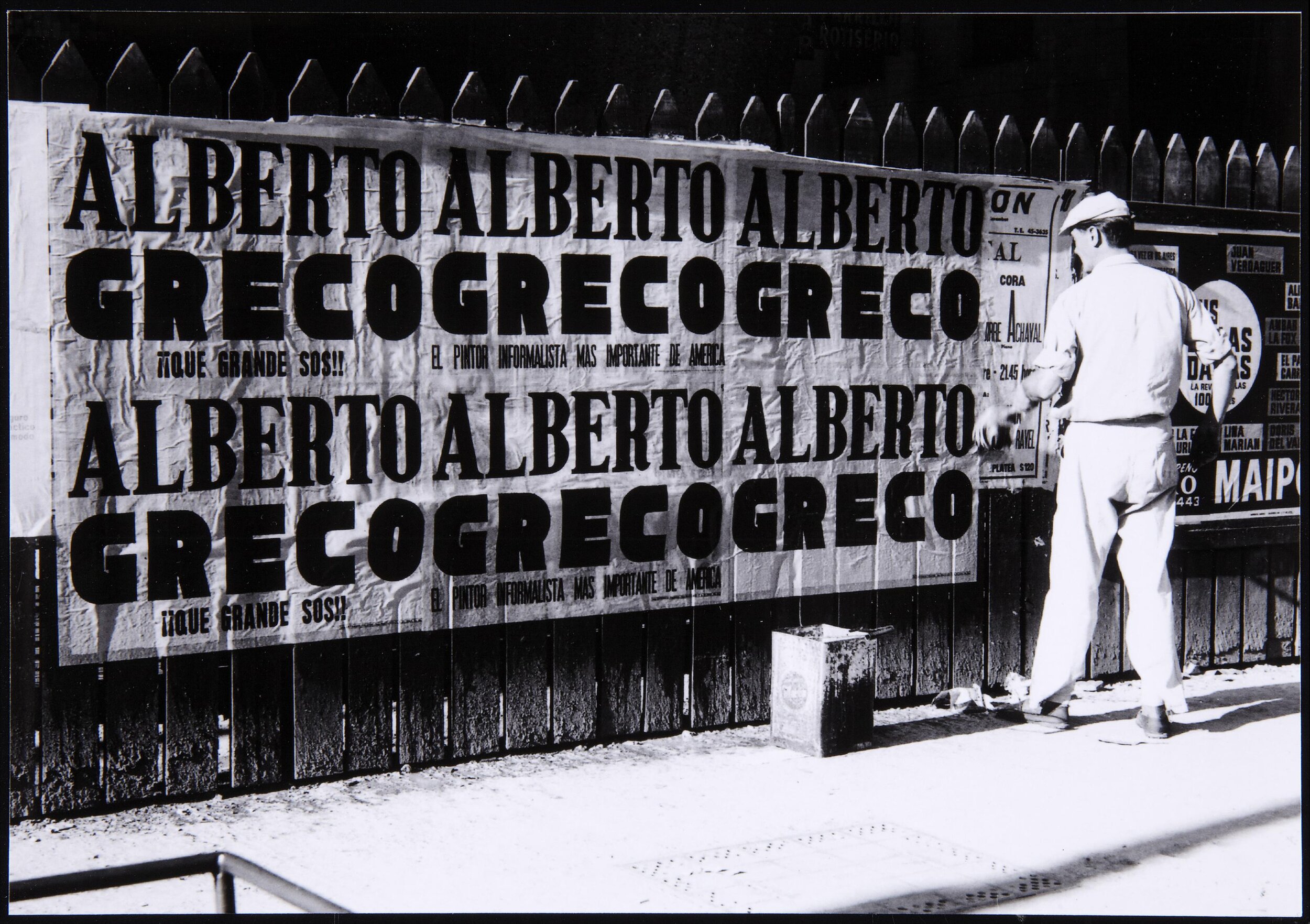

Albert Greco and the Art of Living in the ‘In-Between’.

In the spring of 1956, artist Alberto Greco walked into the Antígona art gallery with six different colored card stocks in glass frames. He had recently returned to Buenos Aires from a year abroad and was invited by the gallerist Mabel Castellanos to exhibit a series of gouache paintings he produced and showed in Paris. The unexpected meeting didn’t stoke the response Greco was expecting; Castellanos demanded he get rid of the cardstocks and bring the works she’d agreed to show.

This was the beginning of a shift away from his work as a painter. The industrial-made card stock was meant to ask spectators to question the definitions of art and the limitations of painting, a medium that Greco increasingly believed to be of less and less relevance. He was slowly leaning into himself as both the artist and the art; the two concepts gradually amalgamated until life became a medium unto itself.

In 1962, Greco wrote his manifesto: Vivo Dito. Dito, which means finger in Italian, alluded to the act of pointing at a person, object, or situation thus changing its context and transforming it into a work of art. In a collection of essays that celebrates the first retrospective of Greco’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, art historian María Amalia García writes about this transition within his body of work:

His body and soul offered themselves as the medium, between this reality and the realm of the spirits of the beyond: the future was foreseen through Greco himself. Alberto was always in an in-between, and, like everyone else was but a little more, in the struggle between life and death.

Steeping in the in-between is what made Greco such a radical. He refused to embrace the static and instead infinitely moved forward. The past left in the past. The future marked by the present. I think that this is distinctly inhuman behavior. It is difficult for most of us to continuously look forward, imagine a more radical way of living, constantly questioning and renewing our old selves.

I was reminded of this after an interview with celebrity chef Dolli Irigoyen went viral. In the middle of a discussion about animal welfare, vegetarianism and veganism on a nationally syndicated daytime talk show, she posed the question, stopping for a moment and pensively furling her eyebrows to let everyone know just how serious she was: “Overnight the entire world decides to go vegetarian, what do we do with all the chickens?”

The conversation leading up to her question was fairly sensible; the panelists circled around how difficult it is to change deeply rooted cultural traditions and personal connections to food. Actress Silvina Escudero pointedly noted that real changes are drawn out even if they are visibly cruel, like boiling sentient beings alive rather than finding a more ‘humane’ method to kill them. Irigoyen’s question completely derailed the debate. Everyone was quickly distracted by a Jurassic Park scenario.

If this sounds like a silly question to you it’s because it is. It’s a futile thought exercise that stands blissfully in the shallow end. It feels me with rage that a role model of national gastronomy hasn’t developed enough insight to understand that food consumption is less about taste and more about geopolitics, economics, and the way both shape culture; or that the value of a particular dish shouldn’t be measured by how delicious it is but rather the ecology that stands behind it. But it surprised me that her question was received with sincerity. Maybe I shouldn’t be—the response is indicative of how so many conceptualize the path to a better future.

Within this logic, the steps we have to take to guarantee a future that pollutes less and democratizes more are chaotic, drastic, and inconceivably different from yesterday and today which, news flash, is the exact future that awaits us if we fail to make massive changes in the ways that we consume, food or otherwise. Look no further than the latest IPCC report on the climate crisis which reveals nothing we don’t already know: emissions continue rising, the climate is warming and we need to decarbonize the global economy and reach net-zero emissions before 2050 if we are to stabilize global temperatures.

It would be much easier to simply ask dumb questions and pay all our attention to chicken population scenarios than to have sensible conversations based on reality . Rather than asking what happens to all the livestock if everyone suddenly decided to stop eating them tomorrow, why not ask ourselves what do we need to do tomorrow so people stop eating so much livestock?

It’s easier to dumb down the conversation because the solutions we need are gargantuan. I’d like to live in a world where people who care about justice and ecology are in positions of power and the ones who don’t want to intellectualize don’t have to. This is precisely the problem. We are so blindsided by the climate, its crisis framed as a problem of individual action and personal consumption, that we fail to recognize that power is the problem. We need to talk less about the climate and more about shifting power structures so that institutions work in the service of the planet and the life that is sustained by it and not the other way around.

After a year of heated public debate, the northeast province of Chaco has announced a deal to erect three massive pork-producing compounds across the state. Each compound will house 2,400 sows, an abattoir, a biodiesel plant, a biodigester and a factory that will turn soy and corn into pig food. These are the first three of an estimated twenty-five compounds that will be constructed across the country. The government of President Alberto Fernandez promises that the intention is to build an ecologically conscious, circular economy that exports 900,000 tons of pork a year. The only thing that is circular is the grains grown on deforested lands to feed animals whose manure will destroy local waterways and soil quality.

Chaco sits in the middle of the Gran Chaco, South America’s second largest forest and an important ecosystem for carbon sequestration. Over the last twenty years, twenty-five percent of the Gran Chaco (in Argentina) has been cleared by Big Ag for grain and livestock production. Clearing land for grain production and introducing massive supplies of manure and waste offers unquantifiable risks to the region's soil and waterways. Governor Jorge Capitanich notes that the deal will “open markets and create employment” but who will benefit from new markets and how will workers be taken care of?

The Argentine-Chilean food tech company Not Co produces a small line of vegan mayonnaise, milk, cheeses, burgers and ground meat. For now, they are available across South America but will soon be gracing US grocery stores. In an old Instagram post, they promise “Change without changing”, an unintentionally tongue-in-cheek way of saying that this is the same shit repackaged under the moniker of ‘sustainability.

Not Co received 30 million dollars in funding from Jeff Bezos in an investment round that won $235 million. Their laboratories mostly utilize pea proteins, another ‘growing market’ in the country that depends on monoculture crops and agrochemicals. As of 2019, 300 million liters of agrochemicals are used annually and directly exposes 13 million, or one-fourth of the population, to dangerous chemicals like Roundup. All over their packaging, Not Co promises to be using less water—what about the water that is polluted by chemical runoff? Why trade off one polluted resource for another? Can’t we imagine food that is better in every single way, not just for the conscience of the final consumer?

These practices cease to exist when we edit the power structures that envelop them. Factory farmed pigs sold cheap for export can not exist if workers are guaranteed living wages and safe working conditions. The marriage of Big Ag and food tech can’t last if the government subsidizes small agroecological family farms and legislates out the use of chemicals that are demonstrable threats to human health and the environment. It’s time to shift the conversation.

When you walk into the main exhibit room of the Alberto Greco retrospective one of the first things you see are six different colored card stocks in glass frames. Eventually, the world caught up to him. I hope it doesn’t take us 70 years to do the same.