Duck Magret in the Middle of a Mayan Jungle

On the responsibilities of good travel.

As the plane circled and dipped down, I could make out the long strips of street lamps and homes dotting the darkness unevenly. “It’s shaped like a snail shell. The city coils around in a big circle,” a friend had told me. I looked out into the cobalt blue sky and imagined a vast city spread over mountain, valley, volcano and jungle.

Once on the ground, we wove in and out of traffic jams through a maze of fancy high rises, warehouse zones and strip malls. The city’s aesthetic changed frequently and without warning. On one corner, two women with long skirts stood outside a convenience store slapping masa loudly in their palms to make tortillas on a chalky comal; just a block down, a tetris of cars negotiated their way through a Domino’s Pizza parking lot. I recognized parts of Los Angeles, La Paz and Buenos Aires as my brain tried to calibrate where it was.

I had been invited to Guatemala to speak about the future of restaurant writing in Latin America, a subject I felt passionately about despite knowing little beyond my own (at the time very new) experiences. They found me and the small website I worked for, paid me compliments and a flight and I didn’t ask many questions. The trip cost more than what I’d made in a year scribbling a column for barely enough money to pay my meals; a detail I kept to myself but made the vacation feel all the more like my dues were being paid off.

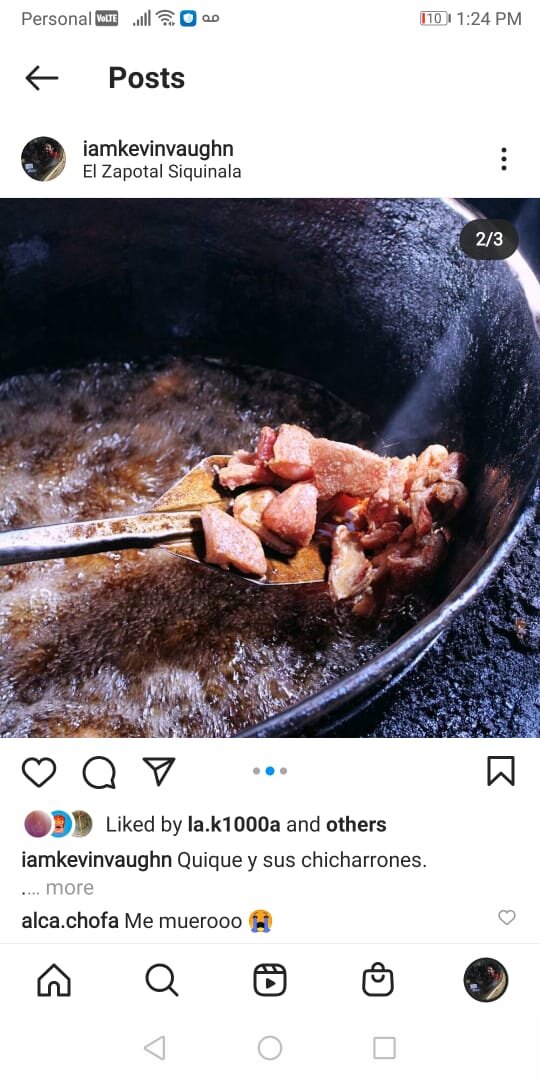

As we drove through a forested highway towards nearby Antigua, I imagined spending the night eating dobladas or chicharron at some nondescript restaurant on a busy street. I could feel the icy bottle of beer to temper the heat of smokey cobanera salsa like the kind my friend Majo had made for me and anticipated the head rush that would come with generous glasses of Zacapa. Instead we walked into a vaguely French, kinda Italian restaurant wedged amongst tables speaking English, Hebrew and German; hostel goers with pants that turn into shorts and travel in hoards seeking out authentic experiences between shots of rum. A table of eight rowdy North Americans suddenly went hush as they all hung their phones above their plates to instagram their raviolis and duck magret.

I don’t remember what I ate although I do remember what everyone else did: pork milanese, macaroni and cheese and mushroom risotto. Just observe what’s going on around you, I kept telling myself until my host suggested ordering a mediocre bottle of Argentine malbec. I preferred a cocktail with a local liquor. The absurdity of paying forty five dollars for a three dollar Luigi Bosca outweighed the novelty of it. The night before my flight, my wife and I had gone out to eat a near identical meal of pasta and red wine to say goodbye to Buenos Aires for the next month, and as I sat at that table it was like there was no real distance between here and there. Internally, I loved to observe all this. A welcome dinner at an overpriced Italian restaurant in a 500 year old town of Mayan and Spanish heritage said as much about my host as it did his preconceived notions of me, a white North American tourist in Central America.

My hosts continued touring me around the capital like this: neapolitan pizza and burrata at an Italian bistro and then more pizza at a New York-style place that looked like an Applebee’s, and some very dry fried chicken and waffles. And I—trying to be gracious to the people who had flown me across the continent—smiled kindly as they attempted to gauge my reactions to each meal while I suggested they “take me somewhere I wouldn’t be able to find on my own”.

I imagined the excitement of walking through the city with wide eyes, stopping anywhere that piqued my interest, of blending myself into the city rather than molding it around me. I imagined eating anything but pizza and macaroni and cheese with people who wouldn’t want to feed me either of those things and not because I have a fetishized notion of authentic food. All food has a meaning attached to it that is authentic to the people and place that consumes it. The penchant for North American-style fast foods and formal Eurocentric restaurants, with no detectable regional imprint, said a lot about the people I was dining with and their perception of me. We could have dined on food specific to that part of the world, whether that was Mayan turkey soup, kak’ik, or chow-mein breakfast tostadas, but instead I had come to Guatemala City to eat mozzarella imported from Italy.

Tourism often feels like theater. It turns entire countries and cultures into digestible soundbites and experiences. As a tour guide myself, I very consciously try to direct tourists and their money towards people and projects that I believe to represent a cross section of the city, towards work that is catered to local culture rather than bending to the service of foreign tastes. Bad tourism, that which extracts the essence of a place and molds it to the visitor, subconsciously simplifying the narrative into a fantasy that which they wish was the reality. Guatemala was just the first time I’d been on the other side of that exchange.

“It is difficult to travel sustainably because as soon as you decide to travel and step on a plane you are already leaving a massive carbon footprint,” starts Mariana Radisic Koliren, founder of Lunfarda Travel. “I want people to understand the impact that tourism has whether that is ecological, like driving around the city in private cars buying one use water bottles, or the social impact too, like buying souvenirs made in China rather than something by a local artisan. Where are they directing their money?”

Radisic has been guiding people around Buenos Aires for the last six years. Initially, she hated taking guests to tourist-heavy areas but today seeks to breathe life back into co-opted spaces. Caminito, for example, a strip of colorful homes that used to serve as tenement houses for the European immigrants that arrived to the city by the thousands at the turn of the 20th century.

“The problem isn’t that we go to places that appear in a Lonely Planet book, the problem is that people go to take pictures and don’t ask why is this here and how did it get to be like this?” continues Radisic. “When I first started guiding, I hated going to Caminito. People came to take pictures and buy imported souvenirs. But I realized that Caminito isn’t the problem. Caminito is where my grandfather’s aunt lived and where he grew up as the son of immigrants in a tenement house. That is a part of my personal story as a porteña, like many others, the granddaughter of a European immigrant. So the problem isn’t Caminito, it is that it has been converted into a Disneyland immigrant sideshow.”

Caminito covers roughly two square blocks of working class La Boca. The influence of Italian immigrants that arrived a century ago is still present but today lives side-by-side with immigration from countries across Latin America that began a half-century after. The story we hear is the former. I wrote extensively about this simple narrative and how Netflix legitimized it in the Buenos Aires episode of Street Food.

“I really feel like people don’t come in search of a story, they want the postcard and the photo,” says Radisic. “Caminito is really emblematic. It is picturesque, people come to take photos and just hear a part of the history. To not go deeper, to not get people to understand that the immigration that happened here was the product of white European supremacy in our society, to not get into that, it perpetuates ideas that are ultimately very damaging to Argentina. When someone comes from the States that is all excited to see the Paris of South America [sic] I love being able to break that narrative.”

Being able to break that narrative depends on an openness. On being a traveler that treads lightly and observes what is in front of them; a tourism that demands from the traveler over constantly catering to the comforts of the tourist. This also requires tour guides to understand their own responsibility and impact on the culture. It requires both to be content with not having experiences that are fully digestible or perfectly instagrammable. Of being okay with maybe only understanding a brushstroke of the much larger picture that is a living, breathing city.

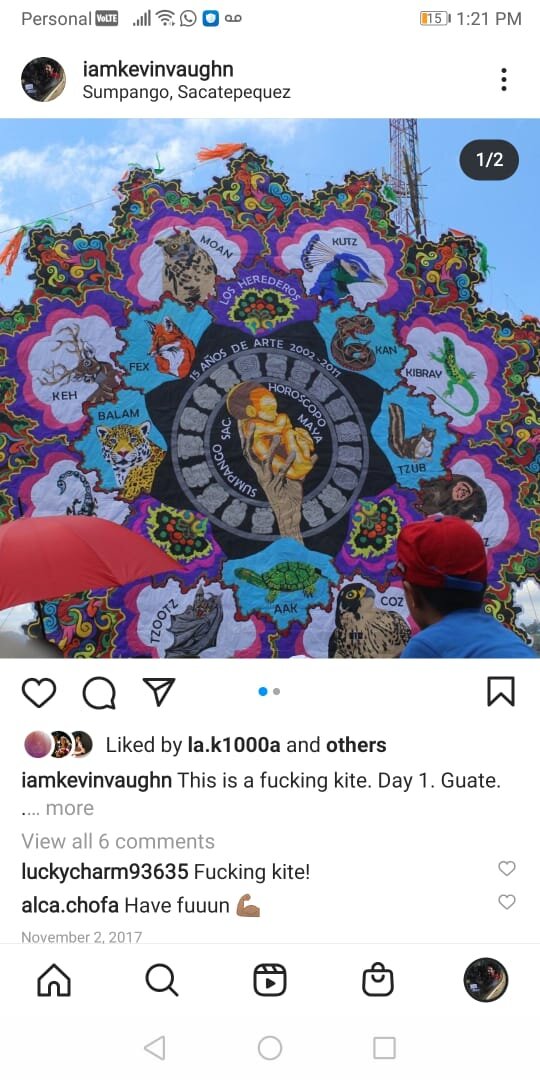

I eventually demanded that my hosts begin to treat me like a guest, which resulted in great meals and imperfect ones, trips to two sprawling neighborhood markets and a food stand two hours out of the city to try chicharron. We also ate a very good cheeseburger topped with chilaquiles verdes. I didn’t get to try a chow mein tostada and not a week passes that I don’t consider a return trip to wander the streets until I find one.